Implications of Section 301 Tariff Actions

Published: Jan 13, 2026

Section 301 tariffs during President Trump’s first term were associated with reducing the U.S. trade deficit with China, though the overall deficit continued to grow. Data suggests tariffs shifted trade flows rather than curbing demand. For CPAs, these insights are key to assessing how renewed tariffs could impact trade patterns, costs and global tax planning.

By Yi Ren, Ph.D., CPA

President Donald Trump, early in his second (non-consecutive) term, moved swiftly to invoke Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 and related tariff provisions in an effort to reshape U.S. trade relationships. In January 2025, he announced a 25 percent tariff on all imports from Canada and Mexico, along with an additional 10 percent tariff on Chinese imports. These measures aim to reduce the U.S. trade deficit, encourage domestic manufacturing and leverage tariffs as a negotiating tool to secure more favorable trade terms. While the final tariff structures remain subject to ongoing negotiations, the policy has begun to fundamentally reshape the dynamics and practices of the global economy.

Supporters argue that such measures enhance national security and revitalize American industry, whereas critics caution that they could escalate trade tensions, raise consumer prices and trigger retaliatory measures from key trading partners.

This article examines the economic effects of tariffs within the broader tax system, focusing on the impact of Section 301 tariff actions on U.S. China trade during President Trump s first term. Although they were not applied exclusively to China, trade between the U.S. and China ranked among the largest in the world during that period. Using historical data, this analysis evaluates the effects of those tariffs on Chinese imports during President Trump s first term to shed light on their broader economic implications. It also provides background and insights to help CPAs better understand the evolution and potential consequences of the current policies and proposals.

Background of Implementation of Section 301 in 2018

The U.S.-China trade tensions in 2018 were primarily initiated by the U.S. under the administration of President Trump, who sought to address perceived trade imbalances and unfair trade practices by China. In 2017, the U.S. imported $463 billion worth of goods from China while exporting only $128 billion to China. This substantial trade deficit was viewed by President Trump and his administration as evidence of unfair trade practices.

In 2018, the U.S. invoked Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 to justify imposing tariffs on Chinese goods deemed unfair or harmful to American businesses. Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 grants the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) authority to investigate and take action to enforce U.S. rights under trade agreements and respond to certain foreign trade practices.

In March 2018, President Trump announced tariffs on steel (25 percent) and aluminum (10 percent) imports from several countries, including China. In June 2018, the U.S. imposed 25 percent tariffs on $50 billion worth of Chinese goods, targeting products in key industries such as robotics and aerospace. Additional rounds of tariffs followed, structured in four lists1:

- 25 percent additional tariff on List 1 covering $34 billion of imports from China, effective July 19, 2018.

- 25 percent additional tariff on List 2 covering $16 billion of imports from China, effective August 23, 2018.

- 25 percent additional tariff on List 3 covering $200 billion of imports from China, effective May 10, 2019.

- 7.5 percent additional tariff on List 4A, covering $120 billion of imports from China, effective February 14, 2020.

The Biden administration left most of these in place. The following analysis reviews the effects of previous tariff actions to offer insight into their broader economic impact.

Trade Deficit

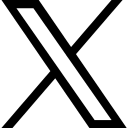

Figure 1 compares the U.S. trade deficit in goods with China (blue bars) to the U.S. trade deficit in goods with the rest of the world (orange bars). The data, sourced from the United States Census Bureau, reveal a clear trend: while the trade deficit in goods with the rest of the world has increased significantly in recent years, the deficit with China has been notably reduced - largely due to tariffs imposed on Chinese imports.

The tariffs on Chinese imports were primarily enacted under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 starting in 2018. By the end of Trump s first term, the average U.S. tariff on Chinese goods had risen from around 3 percent in 2017 to 19 percent on average. During the period, tariffs on goods imported from the rest of the world were more sector-specific and the average U.S. tariff on goods imported from the rest of the world rose slightly from around 2 percent to 3.5 percent on average.

In 2024, the U.S. imported $439 billion in goods from China and exported $143 billion to China, resulting in a $296 billion trade deficit. This represents 24 percent of the total U.S. trade deficit in goods - a sharp decline from nearly 47 percent in 2017. Although broader trends in the Chinese economy may have contributed to this reduction, the decline in the deficit with China began in 2019, indicating that U.S. actions on Chinese imports have played a key role.

*Data source: United States Census Bureau

https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5700.html

https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/historical/gands.pdf

Impact of the Electronic Product Imports

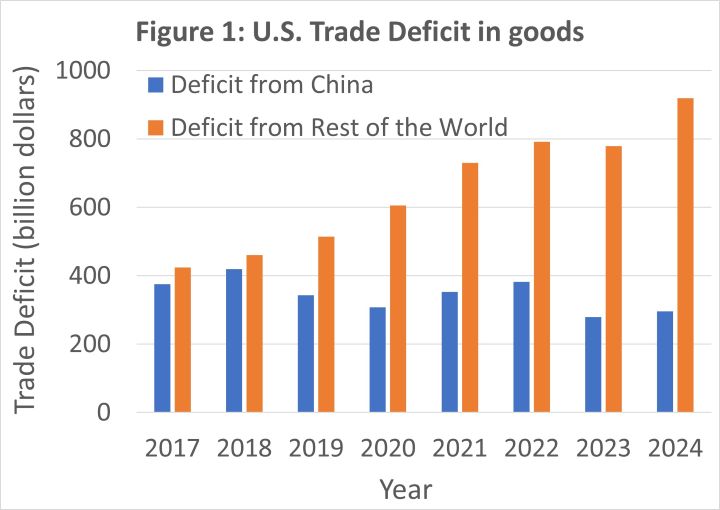

Electronic product was the largest key category of goods imported from China to the U.S. in 2024. Many electronic products from China have been subject to additional tariffs. Figure 2 compares the value of electronic products imported from China (blue bars) with those imported from the rest of the world (orange bars). The graph shows a decline in the value of electronic products imported from China, dropping from $210 billion in 2018 to $167 billion in 2019, a decrease of over 20 percent. In contrast, the value of electronic products imported from the rest of the world rose from $295 billion in 2018 to $317 billion in 2019, an increase of more than 7 percent. This disparity indicates that the actions on Chinese goods had a significant impact on reducing the import of electronic products from China.

*Data source: United States International Trade Commission

https://www.usitc.gov/research_and_analysis/tradeshifts/2023/machinery

https://www.usitc.gov/research_and_analysis/tradeshifts/2020/electronic.htm

Interestingly, as the value of electronic products imported from China decreased from $210 billion in 2018 to $167 billion in 2019, the value of electronic products imported from Taiwan increased from $19 billion in 2018 to $27 billion in 2019 - a 40 percent increase in just one year. Similarly, the value of electronic products imported from Vietnam rose from $12 billion in 2018 to $23 billion in 2019, an impressive 89 percent increase within the same period.2

In addition, the correlation between the value of electronic products imported from China and those imported from Taiwan between 2017 and 2023 exceeds -0.85. Similarly, the correlation between imports from China and Vietnam during the same period exceeds -0.84. This suggests that actions on Chinese goods have significantly benefited Taiwan s and Vietnam's electronic product industries.

Effect of Electronic Tariffs on the U.S. Producer Price Index (PPI)

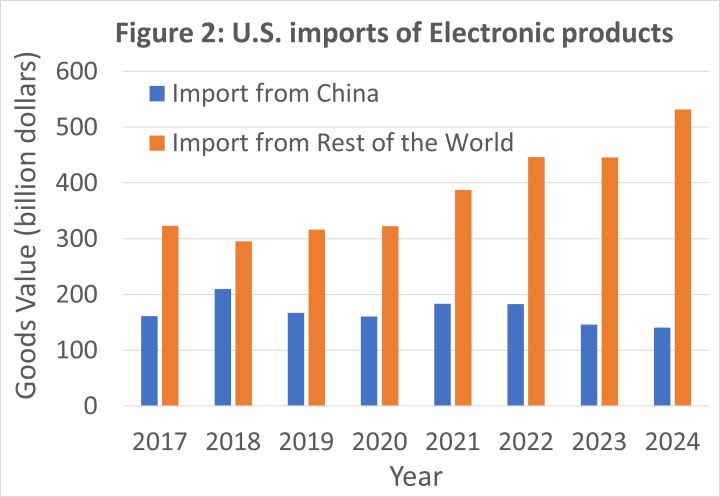

To examine whether tariffs on Chinese goods have affected U.S. market prices, monthly Producer Price Index (PPI) data for electronic products and all commodities were collected from the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) for the period from 2016 to 2024. Both datasets were rebased to a reference value of 100 at the start of 2020.

Electronic products constitute one of the largest categories of goods imported from China to the U.S. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that tariffs have a more pronounced effect on this sector than on other commodity groups. As a result, electronic product prices are expected to be more sensitive on Chinese goods than the prices of other commodities. The difference obtained by subtracting the PPI for all commodities from the PPI for electronic products can provide valuable insights into the potential effects, if any.

Figure 3 shows the difference between the PPI for electronic products and for all commodities. The curve reaches a local minimum around July 2018, followed by a moderate increase and a sharp spike in early 2020, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. The formation of the local minimum and the subsequent gradual rise may be attributed to the imposition of tariffs on China, which likely led to a mild increase in the prices of electronic products compared to other commodities in the U.S. market. After the pandemic s onset, however, the curve shows a steep decline - from 6.6 in early 2020 to -34.6 in 2022 -indicating that the pandemic had far more disruptive effects.

Data Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PPIACO

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PCU334334

Assessing the Impacts of the 2018 Tariffs

This article examines the impact of tariffs imposed on Chinese goods during President Trump s first term. Although they were broadly applied to multiple countries and not exclusively to China, trade between the U.S. and China remains among the largest in the world.

Following the implementation of the tariffs, the U.S. trade deficit with China showed a noticeable decline. However, the trade deficit with the rest of the world continued to expand significantly in subsequent years.

To further assess whether actions taken on Chinese goods have influenced U.S. market prices, an analysis comparing the PPI for electronic products with that for all commodities shows a moderate increase following the enactment of Section 301 in 2018. This indicates that the PPI for electronic products rose more sharply than the overall PPI. The curve also reveals a noticeable spike, largely attributable to the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since his first term, President Trump has refined his tariff strategy, broadening its scope to include a wider range of trading partners. The second-term policy seeks to significantly reduce the trade deficit, among other economic goals. As the administration continues to adjust measures amid ongoing negotiations, it may take considerable time for the full effects of these policies to become evident.

About the Author: Yi Ren, Ph.D., CPA, is professor of accounting at Illinois State University in Normal, Illinois.

End Notes

2 Data from United States International Trade Commission

Thanks to the Sponsors of Today's CPA Magazine

This content was made possible by the sponsors of this issue of Today's CPA Magazine:

Topics: